Last summer, while on a short journey to visit Carcross, the small Tagish town in the southern lake country of Canada’s Yukon Territory, I was returning to Skagway via the South Klondike Highway and noticed a van had stopped, half-way in the middle of the road, and the driver was taking pictures of something.

Now this is quite a common occurrence on this stretch of road, one known for it’s vast amount of black and grizzly bear sighting, especially during the summer. Without thinking too much about this (I had already gandered at a teenage black bear earlier in the day), I started to attempt to pass the unsafely parked van to continue on my way, when about 50 feet in front of me, a gangly, malnourished, and bony-looking cat of some sort ambled across the road. Now I was not close, my eyes may have been playing tricks on me, but it appeared to be some sort of prehistoric cat, even a descendent of a saber-toothed cat. Perhaps it was purple (with spots?) and it definitely looked like a panther that had dragged itself out from a few millennia in the netherworld before melting into the wilderness. Upon returning to Skagway, I told my story of the mutant cat to many, almost all brushing it off as a lynx, or maybe a bobcat. I can tell you for sure this was nearly three times the size of a bobcat (I know the tall-tale is already starting to sound like “the one that got away”) and this was no lynx. The fur, the ears, the body structure; none of it was lynx, and to this day I am convinced I saw something not “normal.”

It May Have Been This….

Interestingly enough, there is a field of study that involves my mutant cat known as “cryptozoology.” Led by Bernard Heuvelmans, a Belgian-French scientist who is now known better as the “father of cryptozoology,” the field involves considering folk-tales, myths, and other here-say as having a basis in truth and, in turn, attempting to locate and identify these mysterious “hidden animals” of nature. Heuvelmans’ book On the Track of Unknown Animals was dismissed across the board by most “mainstream scientists and experts” but did develop a following, leading to the creation of the now defunct International Society of Cryptozoology, using the okapi, originally ridiculed as being a mythological creature, as its symbol.

Around the time the okapi was “discovered,” the world was still open to exploration, and fabled creatures were not necessarily that uncommon to find chewing on a banana tree in your backyard. It was a time when (white) men were still swashbucklers, trudging through the jungles with machete in hand, “taming the savages,” and battling man-eating anacondas, all the while finding ample time to destroy civilizations that already occupied the areas. The okapi, for example, had been noted to exist first by the famous Belgian Henry Morton Stanley, but he was too busy claiming the Congo for the Belgian throne and, concurrently, raping the Congolese of ivory, rubber, and life to corral proof of the creature’s existence. An article from the farcically named American Review of Reviews in 1918 seems to imprudently describe why the okapi’s existence had not been proven until the turn of the 20th century:

“This region is described as one of the most dismal spots on the globe…White men avoid this part of Africa, and that explains why the okapi was not really made known to science until the beginning of the present century.”

As we all know, if “white men” avoid anywhere, science and creativity halt at all costs, and stagnation, with a dose of diabolism and savagery, occurs. Right. But my real point being, even today, there are areas of the globe less traversed than most, examples including the Arctic Circle, Antarctica, and the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Desert. Not to say that giant okapis and Yetis are roaming around the Saudi Arabian sand dunes, but a sense of mystery and the fact that humans cannot claim to know half as much as they even really know about the Earth is a stable truth, with the additional truth that living creatures stranger than any comic book alien have roamed, and some even continue to roam, portions of the globe.

The Songhua River Cactus Porcupine. Please inform me if you ever spot one.

The Pleistocene was an era of ice ages and an era of giant mammals. Mutant creatures more familiarly found in 1950’s science fiction were tromping around ice fields. The giant beaver, a 200-pound beast that to this day is the butt of many jokes, did not become extinct until 14,500 years ago and most likely was hunted by, or at least coexisted with, developing modern Homo sapiens sapiens. Oncorhynchus rastrosus, also known as the saber-toothed salmon, could grow up to 10 feet long and would surely haunt the nightmares of many seafaring children. Giant sloths, giant lemurs, and hairy rhinos were all at the Pleistocene party, and some anthropologists even consider that the hunting of these large mammals created a need for a collaborative effort amongst humans, contributing to the birth of modern “civilization.”

While not many cryptozoologists believe that giant beavers are still lurking in the swamps of northeastern North America, although some claim they do exist, another mammal from the Ice Age, more familiar to the average person, has a much larger log of sightings and hoaxes.

In October of 1899, McClure’s magazine (credited with commencing the muckraking journalism of the Gilded Age and featuring articles from numerous major writers of the era including Willa Cather, Jack London, and Mark Twain) published a small piece titled “The Killing of the Mammoth.” The piece was written by a “Henry Tukeman,” who while travelling through Alaska came into contact with a native man named “Joe,” and after showing Joe a picture of an elephant, together the two found and, eventually, killed the last living mammoth. Proving the unheralded stupidity of the American public, the magazine had labeled the story “fiction” in the table of the contents yet admitted later that the story was written by a short story writer named H.T. Hahn, after receiving numerous angry letters from the public condemning the killing of the mammoth.

While what became known as the “Tukeman Hoax” was pure fiction, other mysterious accounts surrounding wooly mammoths still remain. In 1920, Siberian tribesman claimed to have seen “large shaggy beasts” when questioned by a Russian exploratory team. The bones of pygmy mammoths have been found on the Channel Islands off of California’s coast. Along the Songhua River in Northeastern China, bones of an enormous steppe mammoth have been unearthed, leading scientists to believe this type of mammoth weighed 15 tons, nearly double the size of your average “wooly.” Lastly, on Wrangel Island, a remote Russian island in the Arctic Ocean, what were presumed to be the last living mammoths on earth did not die out until approximately 1700 B.C., an occurrence that may have been related to Inuit travelers following reindeer herds and crossing the frozen ice from Siberia to the historical settlement of Point Hope, Alaska. Mammoths even have the distinction of being the state fossil of Alaska, creating a massive folk hero out of the extinct giant.

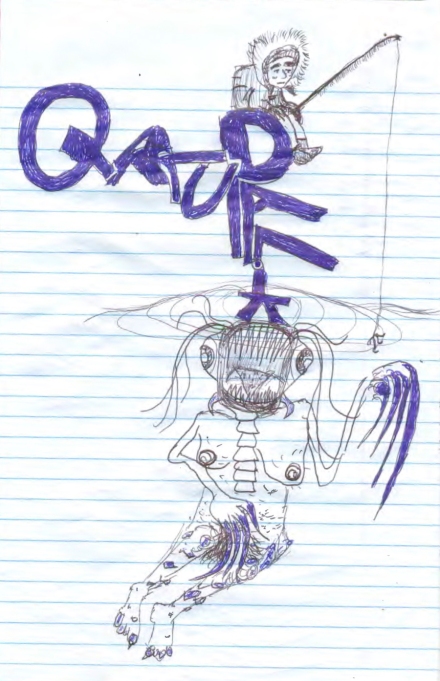

In all of this, I am not claiming that mammoths are still traversing the tundra of Alaska but only reminding that the fact remains the world is a still a wide open area of mystery in many facets. Whether or not a child-snatching sea witch named Qalupalik is lurking off the coast of the Arctic Ocean or whether a giant beaver is leveling forests deep in the blueberry bogs of Maine, improbabilities, myths, and fables do deserve some place in the consciousness of history or, at least, in the jumbled mess that makes up truth.

In Inuit lore, Qalupalik may try to steal your children.